Hebrew Visions of Daniel

Evidence for the Existence of a Non-God

Albert Hayden

The Hebrew visions in the biblical Book of Daniel are exceptional for their predictive prophecies. For centuries, these prophecies have drawn the attention of both scholars and non-scholars alike. Almost all commentators agree that they depict historical persons and events, most notably Alexander and his conquest of the Achaemenid Empire. Despite this consensus, a final analysis of these visions has long remained unaccomplished. This paper presents this analysis. It shows that these visions predicted the precise year for the destruction of Second Temple Jerusalem, at least two centuries in advance. It also shows that they predicted the times and manners of the rise of Islam and the foundation of modern Israel, including the Holocaust. The ultimate source of these prophecies is not the biblical God, but some god-like entity or entities that created these prophecies as a sardonic criticism of human religion. This analysis implies that the principal Abrahamic faiths are consequences of a grand hoax played on humanity by a potentially non-human intelligence, and that the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine is an intentional outcome of this cruel joke. This study nevertheless enables a hope that we may overcome this evil with our own, human good to build a new future together.

The Hebrew visions in the biblical Book of Daniel[1] are an exception in biblical prophecy. Almost all other biblical prophecies are not predictive prophecies. Despite popular theories, the text of the Torah does not conceal future people or future events in any hidden code, and the Hebrew Bible did not, as Christian doctrine has it, secretly foretell the career of Jesus in its stories, laws, histories, or liturgies. Even the “prophecy” genre of biblical literature does not address a predetermined future. Biblical prophets served as intercessors between God and Israel, so they typically pronounced a contingent future, not a certain one. As spokespersons for God, they threatened the Israelites and the peoples that neighbored them with punishment for their transgressions, guiding ancient Israel to a national glory founded on obedience. The intercession of the prophet was often effective, prompting a repentance that stayed divine punishment. Only on occasion was a divine judgment final, and timed predictions concerning a distant, certain future are almost nonexistent. The significant exception to this general rule are the three Hebrew visions appended to the older, fictional, Aramaic core of the Book of Daniel. These visions are timed predictions that correctly depict a distant future, one well after the composition of the book. They predicted the first-century destruction of Second Temple Jerusalem, and they transformed two originally fictional, Aramaic prophecies into timed visions regarding the rise of Islam, World War II, the Holocaust, and the foundation of modern Israel. Though this thesis may seem religious, these observations actually imply that the Hebrew visions of Daniel are a steganographic “Easter egg” that an unknown entity set in the Hebrew Bible to mock its religion, if not all religion. They imply that the modern Abrahamic faiths follow from a grand hoax, of which the present conflict between Israel and Palestine is an intentional result.[2] This conclusion is a serious position, and an urgent concern for the present global civilization.

The Book of Daniel is a book of riddles. It is particularly well known for its six fictional court tales, five of which feature its namesake character, Daniel. Three of these five tales focus on predictive prophecies concealed in riddles, and in all three Daniel deciphers their meaning through his prophetic wisdom. In two of them, Daniel reveals the meanings of a mysterious dream to a fictionalized Nebuchadnezzar. One dream conceals a history of the future in a vision of an idol and a rock that destroys it (Dan 2:31-45).[3] The second conceals the king’s seven-year loss of sanity in a vision of a grand tree chopped down (Dan 4:10-27). The most famous riddle is the third, the “Mene, Mene, Tekel, and Parsin” from the feast of Belshazzar (Dan 5:1-30). This story and its riddle are frequently referenced in Western culture, most notably in a painting by Rembrandt. They are also the origin of the common English idiom “the writing on the wall.” In addition to these court tales, the book has four fictional memoirs that recount visions of the distant future veiled in riddles. These prophecies include cryptic dreams of monstrous beasts, visitations from divine messengers, and mysterious references to large numbers of days (Dan 7:1-28; 9:1-12:13; 8:1-27; 8:13-14; 12:11-12). A notable difference between these latter visions and the prophecies in the tales is the apparent inability of Daniel to decipher their hidden meaning, which he is twice exhorted not to attempt (Dan 7:28; 8:26-27; 12:8-9).

The Book of Daniel is also a complex book. This complexity is illustrated in Table 1. The book consists of two parts, written in different languages, possibly at different times. At its core is an original Aramaic work that is some twenty-four centuries old, dating to the time of the Achaemenid Empire.[4] It consists of the last five court tales and the first vision memoir, arranged into a six-part, thematic chiasm (Dan 2:4b-7:28). This core work consists entirely of religious, historical fiction. This essay calls this core the “Aramaic Daniel.” Added to this Aramaic core is an equal corpus of Hebrew material, written within the same narrative world. Some of the oldest biblical manuscripts still extant attest to the antiquity of this material, the oldest of which dates to the second century BCE. This date is only a terminus ante quem, and the material is likely centuries older. It consists of two parts. The first is a single, fictional court tale prefixed to the Aramaic core, together with a revised introduction to the first Aramaic tale. The second part consists of three Hebrew visions appended to its end. This essay calls these additions the “Hebrew Daniel.”

Together the Hebrew Daniel and the Aramaic Daniel form a new book, with independent literary structures. From a narrative perspective, it restructures the book into two halves of different genres: The first consists of the six court tales and the second, the four visions (Dan 1:1-6:29; 7:1-12:13). An exegetical analysis reveals yet another structure. Exegetically, the expanded book has two sections that meet within the first Hebrew vision. The first section is an expansion of the Aramaic core that extends from the opening of the book through the first half of that vision (Dan 1:1-8:12). A “temple” inclusio bounds this first section: It opens with a fictional attack on the First Temple and closes with a historical attack on the Second (Dan 1:1-2; 8:10-12).[5] The second part consists of the remainder of the Hebrew visions, which constitute a lengthy commentary on the first half of the first Hebrew vision (Dan 8:13-12:13). A “number” inclusio bounds this section: It begins and ends with prophecies that involve large, cryptic numbers of days (Dan 8:13-14; 12:11-12). The three Hebrew visions therefore consist of a main vision and an extended commentary (Dan 8:1-12; 8:13-12:13). Despite their fictional matrix, these three visions conceal in riddles actual, historical people and actual, historical events. This final structure, its precise and accurate timing of the destruction of Jerusalem, and its effect on two end-times prophecies in the Aramaic Daniel are the principal topics of this paper.

Table 1. Content and Structure of Daniel | |||

Genre | Vss. | Section | Theme/Subject |

Tale | 1:1‑21 | ||

Aramaic Core* | |||

2:1‑49 | Age to Come | ||

3:1‑30 | Divine Salvation | ||

4:1‑37 | Divine Sovereignty | ||

5:1‑30 | Divine Sovereignty | ||

5:31‑6:28 | Divine Salvation | ||

Vision | 7:1‑28 | Aramaic Vision: Four Beasts from the Sea and a Little Horn | Age to Come |

8:1‑12 | First Hebrew Vision (Part I): Vision of a Ram and a Goat | ||

8:13‑27 | First Hebrew Vision (Part II): First Number Prophecy | Commentary on the vision of the ram and the goat | |

9:1‑27 | Seventy Sabbatical Cycles | ||

10:1‑11:1 | Third Hebrew Vision (Part I): Third Sabbatical Year | ||

11:2‑45 | Third Hebrew Vision (Part II): Excursus: Decline and Conquest of Ptolemid Egypt | ||

12:1‑13 | Third Hebrew Vision (Part III): Second Number Prophecy | ||

* The opening words of the second court tale is in Hebrew, up to the etnachta at the middle of the fourth verse (Dan 2:1-4a). Apart from this exception, the | |||

That the Hebrew visions of Daniel conceal actual history in riddles is not itself a controversial view. For centuries, all commentators have accepted that these visions depict the conquests of Alexander and their aftermath in cryptic language and symbols. The final vision even includes a detailed historical discourse that is widely noted for its accurate depiction of the Hellenistic Syrian Wars (Dan 11:2-45). No serious, modern scholar disputes these particular facts about the Hebrew visions, and they present no historical anomaly since the terminus ante quem for their composition is the late second century BCE. In addition to these accepted facts, this essay asserts that the three Hebrew visions demonstrably focus on the first-century destruction of the Second Temple, and that the emergence of Islam and the state of Israel are plausible accomplishments of their “large number” prophecies. In short, this paper asserts that the Hebrew visions demonstrably describe and time historical events that postdate their composition by centuries.

Despite this position, this essay does not advocate any religious belief or practice, either new or old. If anything, it calls upon all people to moderate any religious enthusiasm. Though the Hebrew visions of Daniel do point to an intelligent, possibly god-like entity (or entities) with the endurance, knowledge and power to control human history, this fact does not favor any specific religion. Though this entity implicitly presents itself in Daniel as the biblical God of Israel, this presentation is sufficiently incoherent to question its truth. The Hebrew visions of Daniel acknowledge the authority of both the Torah and the Prophets, but neither collection has a divine origin. Both bear clear evidence of a long and complex human origin. In the light of this fact, the authority that these visions confer on the Torah and the Prophets casts doubt on the seriousness of the visions’ religious tone (Dan 9:4-6,11-15; 12:2-3). Prominent elements of sarcasm in the visions also mock religious belief, further amplifying this doubt. Moreover, the entity behind these visions is far from being omnibenevolent or even merely good: It has a clear track record of extreme violence. It planned the destruction of ancient Jerusalem, the long tribulation of the Jewish people, the violence of the Arab conquests, both world wars, and the Holocaust. As its last act in this grand play, this entity has also created the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine, at the expense of both Jew and Gentile. Both Israelis and Palestinians are its victims. One can only conclude that this entity has a low opinion of human religion, and a mixed regard for humanity in general. This entity is not God, as commonly defined. At most it is merely posing as God. Given these conclusions, the Hebrew visions of Daniel are effectively a sardonic coup de grâce in a long, practical joke.

The material in this essay is both demanding and complex. The detailed evidence in and behind this paper requires an understanding of biblical literature, biblical languages, biblical manuscripts, modern history, ancient history, ancient chronology, and even radiodating. This essay also attempts to convey these points as briefly as possible, so its text is dense with details. Readers should therefore review the Book of Daniel in at least one translation before reading this paper, and cross-reference several translations as they ponder its arguments. Footnotes and references will also answer many reasonable questions, the answers to which this paper omits from the main text for the sake of clarity. Readers should also attend to the translated excerpts from the book included throughout this paper, since these translations may differ (with justification) from the common English versions of the Bible. Though nearly all Bible translators are honest and capable linguists, the Hebrew Daniel is typically mistranslated, because its authors wrote it with an intent to confuse readers. Without the observations made in this essay, an accurate translation of Daniel into any language is essentially impossible. The mistranslation of the Hebrew Daniel was therefore inevitable, despite the competent labors of previous translators. The prophecies in Daniel are nonetheless decipherable, and their implications are significant.

Date of Composition

Some of the oldest evidence for the Hebrew Bible attests to the antiquity of the Hebrew Daniel. As shown in Table 2, archaeologists have found, at Qumran, textual fragments from eight distinct Daniel scrolls. None of these pieces form a complete text: They merely preserve clauses, phrases, words and letters from each of their respective manuscripts. Despite their brevity, these fragments bear witness to a relatively stable text, one that Jewish scribes did not substantially change from the Qumran period to the advent of modern printing. These pieces differ little from the standard modern text of the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS), which is based on the medieval Leningrad Codex.[6] The only major innovation in the modern Daniel is the addition of its Masoretic apparatus of niqqud (vowels), versification, cantillation and Ketib-Qere (readings contrary to the text).[7] This apparatus has a medieval origin, and it is not an authoritative representation of the book’s original meaning.[8] It is nevertheless easily distinguished from the original, purely consonantal text. Together the Qumran fragments also bear witness to every major section in the book, including all three Hebrew visions. Portions of the Hebrew Daniel are evident in fragments from six of these scrolls, and we have no compelling reason to think that the other two did not include the Hebrew Daniel.

Based on this evidence alone, the Hebrew Daniel dates well before the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE. The absolute terminus ante quem for any manuscript at Qumran is the destruction of the community in 68 CE, during the First Jewish-Roman War. The latest Daniel manuscripts date to this time. They are 1Q71 (1QDana), 1Q72 (1QDanb), and 6Q7 (6QpapDan).[9] Another late manuscript, 4Q113 (4QDanb), dates to the first half of the first century. We may therefore conclude that the biblical Daniel predates the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE, but other evidence points to an even greater antiquity. Some of the Daniel fragments from the site date to the first century BCE. They are 4Q112 (4QDana), 4Q115 (4QDand), and 4Q116 (4QDane). The oldest text is 4Q114 (4QDanc). It consists of portions of the third Hebrew vision, and it dates to the late second century BCE. This manuscript therefore establishes a reasonable terminus ante quem for the entire Hebrew Daniel of about two centuries before the destruction of Jerusalem.

These paleographic dates are reliable. Though paleographic dating has its critics, radiocarbon dating of the Dead Sea Scrolls has broadly validated the technique. This fact is sometimes challenged, because the precision of typical radiocarbon dates is much too poor to pinpoint the composition of any single manuscript.[10] Any given radiocarbon date may be off by decades, if not centuries. It is not even proper to discuss a radiocarbon date any more than a paleographic date: Both techniques ultimately imply a valid range of calendar dates. Despite this imprecision, the range of radiocarbon dates produced from the examination of twenty-seven scrolls by two laboratories mostly overlap their corresponding paleographic ranges.[11] Most of the few mismatches have credible explanations, and the remaining overlaps are too frequent to be random. They indicate that the paleographic dates are fair estimates of the actual manuscript ages. Thus, when taken as an ensemble, the radiocarbon measurements validate paleographic dating as a technique, even if they do not pinpoint the specific age of any given manuscript. The Hebrew Daniel, then, dates no later than the second century BCE, and it may be much older.

An even more recent study backs this assertion. In “Dating ancient manuscripts using radiocarbon and AI-based writing style analysis,” a cross-disciplinary academic team presented an AI-based date-prediction model, trained with twenty-four manuscript samples and their radiocarbon dates. Though the AI-predicted ages presented in this research are generally older than their corresponding paleographic dates, this result is not the team’s most critical finding to this study. As part of their research, the team radiodated 4Q114 (4QDanc) to 2168 BP with a standard deviation of 15 years, and this measurement firmly plants the composition of the Hebrew Daniel well before the destruction of Jerusalem.[12] It corresponds to a two-sigma calendar date range of 355–285 BCE and 230–160 BCE, which means there is a 98.5% chance that 4Q114 dates to no later than 160 BCE. The same measurement also implies that there is less than a 1 in 1049 chance that it dates to 70 CE or later.[13] There is less than a 1 in 1021 chance that it dates to 32 BCE or later.[14] Should this radiocarbon date withstand further peer review, there is no serious chance that the Hebrew Daniel dates to after the War of Actium or the first-century destruction of Jerusalem.

Table 2. Qumran Manuscripts of Daniel, Dates and Contents | ||

Number (Name) | Paleographic Date | Contents |

4Q114 (4QDanc) | ‘late second century’ BCE ‘no more than about a half century younger than the autograph’[15] | 10:5‑9,11‑16,21; 11:1‑2,13‑17,25‑29 |

4Q116 (4QDane) | ‘large semi-cursive script dated to the early Hasmonean period, i.e., not far from the beginning of the first century BCE’[16] | 9:12‑14,15‑17 |

4Q112 (4QDana) | ‘an elegant formal hand from the late Hasmonean period or the transition into the Herodian period’, ‘middle of the first century BCE’[17] | 1:16‑20; 2:9‑11,19‑49; 3:1‑2; 4:29‑30; 5:5‑7, 12‑14, 16‑19; 7:5‑7, 25‑28; 8:1‑5; 10:16‑20; 11:13‑16 |

4Q115 (4QDand) | ‘an early Herodian formal hand from the last quarter of the first century BCE’[18] | 3:8-10?, 23-25; 4:5-9, 12-16; 7:15-23 |

4Q113 (4QDanb) | ‘developed Herodian formal script’, ‘20-50 CE’[19] | 5:10-12, 14-16, 19-22; 6:8-22, 27-29; 7:1-6,11?, 26-28; 8:1‑8, 13‑16 |

1Q71 (1QDana) | 1:10‑17; 2:2-6 | |

1Q72 (1QDanb) | ‘last phase of the occupation at Qumran’[21] | 3:22-30 |

6Q7 (6QpapDan) | ‘last phase of the occupation at Qumran’[22] | 8:16‑17, 20‑21; 10:8‑16; 11:33‑36, 38 |

Structure and Content of the Hebrew Daniel

The Hebrew visions of Daniel ultimately function as a single literary unit with two parallel structures. One structure is its partition into three visions. Each of these visions is a distinct segment of the main narrative, and each has a unique, superscribed date (Dan 8:1; 9:1; 10:1). The other structure parses these visions into a main prophecy followed by an extended commentary. This basic structure and its parts are shown in Table 3. The main prophecy is part of the extended core of the book (as discussed in the introduction), but since the extended commentary only addresses this prophecy the two effectively constitute a single, separate unit. The commentary also has its own structure, consisting of a four-part chiasm interrupted by a historical excursus. This excursus concerns the decline and fall of Ptolemid Egypt, a matter critical to the meaning of the main vision (Dan 8:13-11:1; 12:1-13; 11:2-45).

The first and principal element of this structure is the symbolic vision of the ram and the goat (Dan 8:1-12). This vision opens with Daniel in a dream, viewing the ancient Achaemenid capital of Susa from the vantage of its citadel. As he surveys the area, he sees a ram with two horns near the Ulai river. This ram thrusts in every direction but the east, and at first no other animal can challenge it. After Daniel takes in this scene, a goat with a single prominent horn appears from the west, out of the setting sun. The goat charges furiously at the ram, throws it to the ground, and tramples it. Despite this victory, the great horn of the goat soon shatters, and four new horns emerge in its place, stretching to the four cardinal directions:

וצפיר העזים הגדיל עד מאד וכעצמו נשברה הקרן הגדולה ותעלנה חזות ארבע תחתיה לארבע רוחות השמים ומן האחת מהם יצא קרן אחת מצעירה ותגדל יתר אל הנגב ואל המזרח ואל הצבי

The male goat truly exalted itself, but at the height of its power the great horn was broken. Then a vision of four rose up in its stead to the four winds of heaven. And from the first of them, a single horn emerged, a strong one, and it grew greater than the south, and the east, and the magnificent horn. (Dan 8:8-9)[23]

From the first of these four, another horn emerges.[24] With this final horn the goat attacks the heavens. It throws stars to the ground, and it tramples them. It then ends the regular burnt offerings, and destroys the Second Temple.

The remainder of the Hebrew Daniel functions as a commentary on this vision. The first part of this commentary is the second half of the same chapter, which is a short exposition from the angel Gabriel on its chief elements (Dan 8:15-27). Though this exposition is brief, it is nevertheless sufficient, together with a general knowledge of ancient history, to decipher most of the vision’s symbols. Gabriel identifies the ram’s two horns as the “kings of Media and Persia,” so the ram represents ancient Iranian civilization (Dan 8:3,20). The first horn is the Median kingdom, and the second horn is Achaemenid Persia. In a parallel fashion, the goat signifies the ancient Greco-Roman civilization of the Classical West (Dan 8:20-21).[25] The first horn on the goat signifies Alexander III of Macedon, and the goat’s attack on the ram signifies his conquest of the Achaemenid Empire. The four horns that replace this first horn signify four Greco-Macedonian successors to Alexander (Dan 8:22). As for the final horn, it signifies a coming king that will destroy Jerusalem and the Second Temple, and this act identifies it as the Roman emperor (Dan 8:22-25).[26]

This final horn-king is a key figure in the Hebrew Daniel, and the remainder of the commentary acts to confirm its Roman identity (Dan 9:26; 11:36-45). After the exposition in the main vision, the commentary times the prophesied destruction of Jerusalem to AM 3830 = 69/70 CE. It accomplishes this feat with the decree of the seventy sabbatical cycles in the second Hebrew vision and the associated material at the start of the third (Dan 9:1-11:1). The following two sections of this paper address this decree and the date it conceals. The historical excursus in the third vision then reinforces the identities of the ram and the goat, clarifies the identity of the first of the four successor horns as Ptolemid Egypt, and clarifies the emergence of the final horn from this horn as the Roman conquest of Egypt in the War of Actium (Dan 11:2-4; 5-35; 40-42).[27] Together these details identify the final horn as the Roman emperor, and the prophesied destruction of Jerusalem as its fall in the First Jewish-Roman War.

Table 3. Structure of the Hebrew Visions | |||

Vision | Ref. (Len.) | Description | |

Second | 8:1-12 (12) | – | Main Vision: the Ram and the Goat These twelve verses are the only symbolic vision in the Hebrew Daniel. They bridge the symbolic Aramaic vision at Daniel 7:1-28 to the discourses of the Hebrew Daniel. |

8:13-27 (15) | A | Gabriel: First Number Revelation This section begins with the prophecy of the 2,300 days (Dan 8:13-14). This opening scene includes three angels, one who asks a question, one who answers, and a third that explains a prophecy to Daniel. Here that third angel is Gabriel. The principal focus of his exposition is the vision of the ram and the goat, and the events leading to the destruction of Second Temple Jerusalem. | |

Third | 9:1-27 (27) | B | Gabriel: Decree of the Seventy Sabbatical Cycles After its superscription, this vision opens with Daniel petitioning God in prayer for the restoration of Jerusalem (Dan 9:2-19). It ends with the appearance of Gabriel, who reveals a divine decree, issued just before the petition, that permits the restoration of Jerusalem for seventy sabbatical cycles, after which the coming king of the main vision will destroy it (Dan 9:24-27). |

Fourth | 10:1-11:1 (22) | B | Man in Linen: Vision of the Third Sabbatical Cycle This vision opens with Daniel mourning an unstated loss. While standing on the edge of the Tigris river, he has a vision of an unnamed “man in linen.” Various riddles in this section imply that Daniel is mourning the decree revealed in the previous vision, and the man in linen is responding to the prayer that preceded it. These riddles also tie the third sabbatical year of the seventy cycles to the expedition of Cyrus the Younger. |

11:2-45 (44) | – | Excursus: Decline and Conquest of Ptolemid Egypt An excursus on the decline and conquest of Ptolemid Egypt interrupts the revelations of the man in linen. A resumptive repetition and a distinct chiastic structure set this discourse apart from the rest of the Hebrew Daniel. | |

12:1-13 (13) | A | Man in Linen: Second Number Revelation The principal feature of this section is the prophecy of the 1,290 days and 1,335 days, with which it ends (Dan 12:11-12). As in the opening prophecy of the commentary, the scene includes three angels, one who asks a question, one who answers, and a third that expounds the vision to Daniel. The angel that expounds this meaning is the man in linen. This exposition focuses on the tribulation following the destruction of Second Temple Jerusalem. This prophecy alludes to the “time, two times and half a time” of the Aramaic vision (Dan 12:7; 7:25). | |

Style and characters are among the literary elements that establish and support the identified structure of the Hebrew Daniel. The key element that sets the main vision apart from the rest is its dramatic symbolism. Though this symbolism parallels the style of the Aramaic vision, it is unique within the Hebrew Daniel (Dan 7:1-28). The other visions are all discourses. Other elements that support this structure are the two distinct angelic informants. These angelic informants are Gabriel and the man in linen, two fictional characters drawn from wider Jewish lore.[28] These two angels divide the commentary into two parts: Gabriel is the informant in the first part, and the man in linen is the informant in the second (Dan 8:16; 9:21; 10:5; 12:6-7). The prophecies of the large numbers also have notable parallel elements. These elements are the appearance of additional angels and a question and answer about the fate of the Jewish people (Dan 8:13-14; 12:5-12).

Inclusios also have a substantial role in this structure. The most prominent is the inclusio of the cryptic numbers that set the commentary apart from the expanded core of the book (Dan 8:13-14; 12:11-12). Another inclusio is the repetition of the first year of Darius (Dan 9:1; 11:1). This repetition bookends the chronological core of the commentary, which has a common focus on the decree of the seventy sabbatical cycles (Dan 9:1-11:1; 9:20-27). Another inclusio is the repeated reference to the resolution of an angel that bounds the excursus on the decline and conquest of Ptolemid Egypt. Before the excursus begins, the man in linen mentions his stand on behalf of Darius the Mede, and after it ends he mentions the stand of Michael on behalf of the Jewish people (Dan 11:1; 12:1).

This inclusio is not the key feature that sets the excursus apart from the rest of the commentary. That feature is its own internal chiasm, shown in Table 4. This chiasm begins with a prologue that bridges the time of the vision to the rise of Ptolemy and Seleucus (Dan 11:2-5). The second part of this chiasm then moves forward to Ptolemy III and the ascendancy of Ptolemid Egypt (Dan 11:6-9). The third part (with two sections) concerns Antiochus III, and his two attempts to conquer Egypt (Dan 11:10-17). The fourth part concerns the transition from Antiochus III to his son Antiochus IV, including a brief mention of Seleucus IV (Dan 11:18-24; 11:20). The fifth part (again with two sections) concerns Antiochus IV, his two attempts to conquer Egypt, and a synopsis of his associated war against Judea (Dan 11:25-35). The sixth section concerns Augustus, his hatred for Egyptian religion, and his conquest of Egypt in the War of Actium (Dan 11:36-42). The seventh and final section is an epilogue that returns the excursus to the main topic of the three visions, the destruction of Second Temple Jerusalem (Dan 11:43-45).

The principal topic of the excursus is therefore the decline and conquest of Ptolemid Egypt. Its material chiefly concerns four kings. The first is Ptolemy III, who led the Ptolemid kingdom to its apex. The second and third are Antiochus III and Antiochus IV, both of whom attempted to conquer Egypt and failed. The fourth is Augustus, who did conquer Egypt. References to all other kings and events are incidental to these men, and to their role in the decline and conquest of Egypt. This includes the synopsis of the Hasmonean revolt, and the even briefer reference to the destruction of Jerusalem (Dan 11:31-35; 43-45). The excursus also omits substantial periods of history irrelevant to its central topic. Its opening is a mere abstract of the long history from Artaxerxes II to Ptolemy. Its text makes no mention of Ptolemy II, and it does not mention the first two Syrian Wars. Its overview of Seleucus IV and his twelve-year reign consists of a single verse. It almost wholly omits the history from Antiochus IV to Augustus. The excursus nonetheless fulfills a critical function. Without the excursus, the emergence of the final horn from the first of the four successors has an unclear meaning. With the excursus, this emergence firmly identifies the final horn with Rome.

Table 4. Structure of the Excursus on Ptolemid Egypt (Dan 11:2-45) | |||||

Vss. (Len.) | Subject | ||||

2-5 (4) | A | Prologue (Artaxerxes II to Ptolemy and Seleucus) | |||

6-9 (4) | B | Ptolemy III and Ptolemid Egypt Ascendant (Third Syrian War) | |||

10-17 (8) | C | 10‑12 (3) | C1 | Failure in the Fourth Syrian War | |

13‑17 (5) | C2 | Success in the Fifth Syrian War | |||

18-24 (7) | X | Transition (Seleucus IV, Pergamon, and Antiochus IV) | |||

25-35 (11) | C | Antiochus IV | 25‑28 (4) | C2 | Success in the Sixth Syrian War |

29‑35 (7) | C1 | Failure in the Sixth Syrian War | |||

36-42 (7) | B | Augustus and Ptolemid Egypt Conquered (War of Actium) | |||

43-45 (3) | A | Epilogue (Destruction of Jerusalem) | |||

Mistranslation and misinterpretation of the excursus obscure its depiction of Augustus and the War of Actium. The excursus begins this depiction at Daniel 11:36, where it describes the contempt the final horn-king has “for every god” and his many blasphemies (Dan 11:36-39). Most commentators misunderstand this description as his opposition to Judaism and the biblical God, but the excursus actually refers to the contempt Augustus had for Egyptian religion. The “god of gods” against whom he speaks “horrendous things” is a sarcastic reference to the pretensions of the pharaoh, then Ptolemy XV Caesar (Caesarion).[29] Augustus himself personally refused divine honors as pharaoh, and the foreign “god of fortresses” that he honors is Zeus Eleutherios. This Athenian Zeus was the principal basis of the imperial cult in Egypt.[30] At Daniel 11:40 the excursus begins its depiction of the War of Actium, but a common mistranslation of the title “the king of the treasure” (Heb.: מלך הצפון) obscures this fact.[31] This title is a pun on “the king of the north,” another title which the excursus gives to the Seleucid dynasty. These two titles share an identical spelling, so they are indistinguishable without written vowels or an unbroken reading tradition, which does not exist.[32] The title “king of the treasure” emphasizes the successful Roman conquest of Egypt and the seizure of its riches, in order to mock the previous Seleucid failures. A better translation is:

ובעת קץ יתנגח עמו מלך הנגב וישתער עליו מלך הצפון ברכב ובפרשים ובאניו רבות ובא בארצות ושטף ועבר ובא בארץ הצבי ורבות יכשלו ואלה ימלטו מידו אדום ומואב וראשית בני עמון וישלח ידו בארצות וארץ מצרים לא תהיה לפליטה

For at the fated time, the king of the south will aggravate him, so the king of the treasure will storm against him with riders, horsemen, and with many ships. Then he will enter the lands, sweep over, and pass through. He will even enter the beautiful land as many lands fall. These lands, however, will escape from his power: Edom, Moab, and the best land of the Ammonites. Yet he will extend his power throughout the lands, and the land of Egypt will not become an exception. (Dan 11:40-42)

This passage accurately describes the War of Actium. It correctly observes the prominent role of ships in the Battle of Actium, and that Augustus did not annex the Nabatean Kingdom. (The Nabateans ruled “Edom, Moab and the best land of the Ammonites”).

Another mistranslation obscures the destruction of Jerusalem at the very end of the excursus. The destruction of the temple is mentioned in its very last verse, but the English versions typically translate it as if it depicts the destruction of the final king, and not the temple:

ומשל במכמני הזהב והכסף ובכל חמדות מצרים ולבים וכשים במצעדיו ושמעות יבהלהו ממזרח ומצפון ויצא בחמא גדלה להשמיד ולהחרִים רבים ויטע אהלי אפדנו בין ימים להר צבי קדש ובא עד קצו ואין עוזר לו

Then he will rule over treasures of gold and silver, and over all the precious things of the Egyptians. Yet when the North Africans and the Kushites are within his footsteps, reports from the east and from the north will terrify him, so he will go out, with wrath enough to destroy and to exterminate many. And he will pitch the tents of his destruction between the seas, against the beautiful holy mountain. And it will come to its end, and no one will save it. (Dan 11:43-45)

This alternate translation interprets “the beautiful holy mountain” (Heb.: הר צבי קדש, a reference to the Temple Mount) as the antecedent of the pronominal suffixes in the clauses “and it will come to its end, and no one will save it” (Heb: ובא עד קצו ואין עוזר לו, emphasis added). The standard translation is technically correct, but it does not fit its context. On the one hand, the gender and number of the suffixes match a reference to the king, so he could be the antecedent of these suffixes. On the other hand, the fall of the final horn is inconsistent with both the main vision and the discourse that follows. The third vision immediately transitions from this event to the Jewish tribulation, and in the main vision, the goat and its final horn prosper without any evident downfall after the destruction of the temple (Dan 12:1; 8:12). The more logical antecedent is the Temple Mount.

The excursus therefore does much to clarify the main vision. First, it reinforces the identities of the ram and the goat as Achaemenid Persia and the Classical West (Dan 11:2-4). Second, it confirms the identity of the goat’s first horn, and clarifies the identities of the four successor horns. The first horn is Alexander, and the first of the four horns is Ptolemid Egypt (Dan 11:3-4; 11:5). Ptolemid Egypt is also the “kingdom of the south,” and Seleucid Asia is the “kingdom of the north” (Dan 11:5-35). These titles reflect two of the four cardinal directions to which the four successor horns grow (Dan 8:8).[33] Third, it elaborates on the identity of the final horn, and it clarifies its emergence from the first of the four horns as the Roman conquest of Ptolemid Egypt (Dan 11:36-39; 11:40-43). The final horn in the main vision is Rome.

Dating the Destruction of Jerusalem

The Hebrew Daniel has more chronological detail than the Aramaic Daniel, and this difference is meaningful. Apart from a single exception, all dates in the book are in the Hebrew Daniel.[34] Some of these dates have a hidden meaning, and among them are its opening and closing years. The opening date of the book is the third year of Jehoiakim, king of Judah, and the closing date of the book is the third year of Cyrus, king of Persia (Dan 1:1; 10:1). Both kings are based on historical persons, and when we read these dates as historical, the result has exegetical significance. In actual history, the first date is AM 3156 = 606/5 BCE and the second is AM 3226 = 536/5 BCE.[35] These dates are exactly seventy years apart, and this span is no accident. The central section of the Hebrew Daniel at Daniel 9:1-11:1 begins with a reference to two prophecies of Jeremiah, both of which decreed seventy years of desolation on Jerusalem that end with the fall of Babylon (Dan 9:2; Jer 25:11-12; 29:10-14). The actual Neo-Babylonian Empire fell in AM 3223 = 539/8 BCE, less than fifty years after the first desolation of Jerusalem in AM 3174 = 588/7 BCE. The historical prophecy, then, did not have an exact accomplishment. The prophecy nevertheless dates to the fourth year of Jehoiakim, one year after the opening date that the Hebrew Daniel adds to the book (Jer 25:1; Dan 1:1). The dates of the expanded narrative therefore align with an exact accomplishment of this prophecy.

This subtle feature of the book is more than a mere curiosity. It is an intentional and sarcastic dig at biblical prophecy that draws attention to the historical failure of a timed biblical prediction. It also implies a similar failure within the modified fictional universe of the book, which explains the opening of the second Hebrew vision. In that opening, the fictionalized conquest of Babylon under Darius the Mede prompts Daniel to review the prophecy of Jeremiah and to pray for the redemption of Jerusalem (Dan 9:1-19). The relevance of the prophecy to the vision is not clear from the immediate context, but the fictional seventy-year span of the book explains it. The fall of Babylon confuses the character Daniel precisely because it occurs before the accomplishment of the seventy years (Dan 5:30-31). Daniel therefore judges that God has changed his mind about Babylon, so he pleads with God to change his mind about Jerusalem (Dan 9:3-19).

The response to this prayer is the decree of the seventy sabbatical cycles. As Daniel prays, the messenger Gabriel appears, and he announces a message from God. He tells Daniel that God has decreed the restoration of Jerusalem, yet he also proclaims its eventual destruction after seventy sabbatical cycles.[36] In this message, Gabriel identifies its destroyer as “a prince, the coming one,” a reference to the final horn in the main vision:

שבעים שבעים נחתך על עמך ועל עיר קדשך לכלא הפשע ולחתם חטאות ולכפר עון ולהביא צדק עלמים ולחתם חזון ונביא ולמשח קדש קדשים ותדע ותשכל מן מצא דבר להשיב ולבנות ירושלם עד משיח נגיד שבעים שבעה ושבעים ששים ושנים תשוב ונבנתה רחוב וחרוץ ובצוק העתים ואחרי השבעים ששים ושנים יכרת משיח ואין לו והעיר והקדש ישחית עם נגיד הבא וקצו בשטף ועד קץ מלחמה נחרצת שממות והגביר ברית לרבים שבוע אחד וחצי השבוע ישבית זבח ומנחה ועל כנף שקוצים משמם ועד כלה ונחרצה תתך על שמם

Seventy sabbatical cycles are conceded to your people and to your holy city, to end the transgression, to seal an offence, and to atone an iniquity; to bring in eternal righteousness, to confirm a vision and a prophet, and to anoint a most holy place. Know and understand that from the pronouncement of the word to rebuild Jerusalem once more until an anointed one becomes a prince there will be seven sabbatical cycles, and for sixty-two cycles it will return, for it will be rebuilt with a public square and an aqueduct despite the distress of those times. But after the sixty-two cycles an anointed one will be cut off, and he will have nothing. For an army of a prince, the coming one, will destroy the city and the holy temple, and its end will be as a flood, for desolations are decreed until the end of a war. Yet a covenant among the masses will become strong for one cycle, and in the middle of the cycle it will put an end to a sacrifice and an offering. But on account of a bird of abominations it will be put to shame, even as far as a complete destruction. For what is decreed will be poured out upon a desolation. (Dan 9:24-27)

This response is profoundly sarcastic. Though Gabriel calls Daniel “greatly beloved,” God nonetheless rewards his intercession with the promise of a second destruction of his beloved home. Despite the irony, this decree is the most critical feature of the Hebrew Daniel. It precisely and correctly dates the destruction of Second Temple Jerusalem, the main topic of the Hebrew visions. According to Gabriel, the divine decree grants Jerusalem a period of reprieve from its future destruction. This period lasts for seventy sabbatical cycles from this “pronouncement of the word to rebuild Jerusalem,” which is the date of the vision (Dan 9:1,23-25). The decree therefore dates the destruction to the first postsabbatical year after this period, when the reprieve is no longer effective. That year is AM 3830 = 69/70 CE.

This precise, implicit date is not obvious, but it follows from a nearly transparent riddle. An immediate problem with the timeline of the decree is the fictional nature of Darius the Mede: At a surface glance, the vision dates to the first year of his fictional reign, which is incoherent with any actual, historical timeline (Dan 9:1). This problem nevertheless has a compelling solution: The date superscribed to the vision is a riddle. The Hebrew text of this superscription has two plausible interpretations shown here in bold font:

בשנת אחת לדריוש בן אחשורוש מזרע מדי אשר המלך על מלכות כשדים

In the first year of Darius ben Xerxes from the race of the Medes who (that) was made to reign over the kingdom of the Chaldeans. (Dan 9:1)

The difference between these translations is the chosen antecedent of the relative pronoun (Heb.: אשר), for which this needlessly complex text permits two alternatives. The first possibility is the name “Darius ben Xerxes” (Heb.: דריוש בן אחשורוש). In this case, the better translation of the pronoun is “who,” and “Darius ben Xerxes” is a Mede who becomes king of Babylon. He is therefore the fictional “Darius the Mede” from the court tales. The other possible antecedent is “the race of the Medes” (Heb.: זרע מדי). In this case, the proper translation of the pronoun is “that,” and “Darius ben Xerxes” is a Persian, the actual “race of the Medes” that conquered Babylon (“the kingdom of the Chaldeans”).[37] In this second interpretation, the otherwise gratuitous reference to Xerxes makes sense: “Darius ben Xerxes” is Darius II, the grandson of Xerxes, the historical Achaemenid king. This name notably evokes the conflict between Persia and the West, a prominent theme in the main vision (Dan 8:5-8). Though the use of an avonymic is uncommon, the significance of Xerxes to this conflict justifies it.[38] Xerxes was the second Persian king to invade Greece. The name also distinguishes Darius II from Darius I, the father of Xerxes and the first Persian king to invade Greece. This interpretation is credible within its context, and it dates the vision to the sabbatical year AM 3339 = 423/2 BCE, the first Hebrew calendar year of Darius II.[39] The addition of four hundred and ninety-one years to this date yields the postsabbatical year AM 3830 = 69/70 CE, the very year the Romans destroyed Jerusalem.

By any reasonable standard, the success of this interpretation demonstrates its correctness. This interpretation is not arbitrary: Daniel is a book of riddles, so a hidden date is plausible. The proposed date also follows from one of two plausible readings of the superscription. It also explains the needless complexity of that superscription. (A mere “in the first year of Darius the Mede” should have sufficed.) It explains the gratuitous reference to Xerxes, a name that occurs nowhere else in Daniel. The proposed date correctly aligns with the count of sabbatical years. (As explained below, it may also align with the count of the Second Temple Jubilee.) It gives the correct date for the predicted event. The random accomplishment of this entire feat is almost impossible: Authorial intent is far and away the superior hypothesis.

Only one fact seriously challenges this conclusion: This vision predates the destruction that it correctly times by at least two centuries, if not more. One corollary of causality is that no record of an event can precede its occurrence, and for this reason any mention of an event generally establishes the terminus post quem for the composition of a text. The fact, then, that the second Hebrew vision correctly dates the destruction of Jerusalem should date its composition to no earlier than 70 CE. The physical evidence of the Qumran fragments, however, contradicts this conclusion, and dates the Hebrew Daniel to absolutely no later than the second century BCE. This contradiction leaves only one logical alternative: The Hebrew Daniel presents to us the past intent of an entity with the knowledge, power, and endurance to effect it. The paleographic analysis of the Qumran Daniel fragments is not in error, and the translations presented above are valid. The analysis that leads to the year AM 3830 = 69/70 CE is also too simple to reject its plausibility. To reject the analysis on the grounds that the implicit entity is impossible constitutes an appeal to consequences. To assert that this entity is implausible without direct observation is special pleading.

The prophecy of the seventy sabbatical cycles therefore predicted the future, and an analysis of the third Hebrew vision only amplifies this conclusion. This vision is the closing story of the book that dates to “the third year of Cyrus, king of Persia” (Dan 10:1). Given its seventy-year span from the opening date of the book, this superscription no doubt refers to the third year of Cyrus the Great. Various clues within the vision nonetheless indicate that it refers to more than this one historical date. The key clue is the number three at the start of the historical discourse on Ptolemid Egypt. The authors of the Hebrew Daniel bound this discourse with an inclusio that concerns angels. Before it begins, the man in linen (the visiting angel in the vision) states that he stood up for Darius the Mede; after it ends, he states that the archangel Michael will stand up for the Jewish people (Dan 11:1; 12:1). Within these bounds, at the very start of the discourse, stand the suggestive words “and now I will tell you the truth,” and this sarcastic remark is indeed serious (Dan 11:2). Unlike the rest of the vision, nothing in the excursus is veiled with the fictional matrix of the book. In the very same verse, the man in linen gives the number of Persian kings between the vision and the rise of Alexander as three (Dan 11:2). On the assumption that this number is historical, these three kings are Artaxerxes III, Arses and Darius III. This number therefore implies that the vision actually dates to the reign of Artaxerxes II.

Dating the vision to the reign of Artaxerxes II may seem inconsistent with “the third year of Cyrus” superscribed to the vision, but other elements make sense of this discrepancy. These elements are a “commander of Persia,” a “commander of Ionia,” and an imminent war that demands the immediate attention of the man in linen (Dan 10:13,20).[40] Commentators generally interpret these “commanders” as spiritual beings, but they probably signify actual people. If the “third year of Cyrus” actually refers to the third year of Artaxerxes II, then it corresponds to either AM 3359 = 403/2 BCE or AM 3360 = 402/1 BCE.[41] These dates are significant: In AM 3360 = 402/1 BCE Cyrus the Younger, the brother of Artaxerxes, led an expedition against him, with an intent to seize the Achaemenid throne. Given this alignment, the “commander of Persia” is arguably Cyrus, and the imminent war is his expedition against Artaxerxes. As for the “commander of Ionia,” this title arguably refers to Xenophon, a Greek leader that aided Cyrus in his campaign. The “Cyrus,” then, in “the third year of Cyrus, king of Persia” may be an ironic reference to Cyrus the Younger, as much as a reference to Cyrus the Great.

The confirmation of this interpretation lies in an additional riddle. At the opening of the vision, Daniel twice reports that he has mourned and fasted for “three full weeks,” and the needless repetition of this phrase points to a hidden meaning (Dan 10:2-3). The text never states what prompted Daniel to mourn, but the coming destruction of Jerusalem promised in the second vision offers sufficient reason (Dan 9:24-27). Since the word for “week” in Hebrew and Aramaic also means “sabbatical cycle,” this context suggests that Daniel has mourned, not for three seven-day weeks, but for the first three of the prophesied sabbatical cycles. If so, the “historical” date of the vision is the third sabbatical year of the seventy cycles, or AM 3360 = 402/1 BCE, when Cyrus attacked Artaxerxes. This notice therefore confirms the ironic reference to Cyrus in the vision’s date, the historical interpretation of the three Persian kings before Alexander, and the imminent war with the “commanders” of Persia and Ionia. The interpretation of “Darius ben Xerxes” as Darius II explains more in the Hebrew visions than just the decree of the seventy sabbatical cycles.

The only element in the third Hebrew vision that challenges this conclusion is the “twenty-one days” for which the “commander of the kingdom of Persia” delayed the man in linen (Dan 10:13). This challenge is a sound concern, but the general success of this analysis casts doubt on its significance. In a book of riddles, the probability that these “days” have some alternate, hidden significance is too high to dismiss the extreme improbability that the alignments observed above are random. Moreover, this notice of “days” is not entirely coherent, much like the incoherence between the fictional Darius the Mede and seventy historical sabbatical cycles. The man in linen states that during this time he was left with the “kings” of Persia, a plural noun that does not fit twenty-one days during the third year of the current king (Dan 10:13).[42] A possible (if not probable) solution to this incoherence is yet another riddle, one that equates narrative days with historical years. From this perspective, there is no incoherence: The “twenty-one days” refer to the twenty-one-year life of Cyrus, and the “kings of Persia” refer to Darius II and Artaxerxes II. The mere fact that this proposal solves these problems is not sufficient to confirm it: The evidence that motivates a hypothesis cannot also prove it. To confirm this proposal, this essay must show that the Hebrew visions use narrative days elsewhere to signify historical years, which they do. That use exists in the prophecies of the large, cryptic numbers, which this essay addresses in the second to last section below.

Decree of Darius, the Mission of Nehemiah, and the Jubilee

The seventy sabbatical cycles are not a simple duration between the first year of Darius II and the destruction of Jerusalem. The decree divides them into successive periods of seven cycles, sixty-two cycles, and one cycle (Dan 9:24-27). It also divides the final cycle in half (Dan 9:27). These divisions result in at least five milestones:

1. | Start of the seven cycles: AM 3339 = 422/1 BCE | |

2. | Start of the sixty-two cycles: AM 3389 = 373/2 BCE | |

3. | Start of the final cycle: AM 3823 = 62/3 CE | |

4. | Middle of the final cycle: AM 3826 = 65/6 CE | |

5. | First year after the seventy cycles: AM 3830 = 69/70 CE |

A full list of the milestones in the decree, including these five, is given below in Table 5. The meaning of the final three above all make sense in terms of the First-Jewish Roman War. The fifth milestone clearly marks the destruction of Jerusalem itself. The fourth milestone marks when the sacrifices for the emperor ended at the temple, starting the war (Dan 9:27; Josephus, J.W. 2.409). The third milestone, when an “anointed is cut off,” marks the removal of Ananas ben Ananas from the office of high priest (Dan 9:26; Josephus, Ant. 20.197-203). The high priest, like the ancient Israelite kings, was an “anointed” official (Lev 4:3,5,16; 6:15).

The second milestone is not as straightforward. It marks the end to the mission of Nehemiah in the thirty-second year of Artaxerxes II. Nehemiah rebuilt Jerusalem and restored its regional significance, which elevated the status and prominence of the high priest. The high priest is therefore the “anointed” in the decree who becomes a prince at this time (Dan 9:25). The alignment between Nehemiah and this milestone is not obvious, because the vision contradicts the current consensus on the end of his mission. Today, most interested scholars (if they accept Nehemiah as a historical person) date the mission of Nehemiah to the reign of Artaxerxes I, but this consensus is not decisive. It contradicts the documented opposition of Artaxerxes I to the refortification of the city, and it rests almost entirely on certain names (other than Nehemiah) in an Aramaic papyrus from Elephantine (Ezra 4:6-24).[43] This evidence on which it rests is not only circumstantial, it is also incomplete. The current literature on the topic notably neglects the possible relevance of the war between Egypt and Artaxerxes II to the date of the mission.[44] The only direct evidence for the date of the mission is the biblical text, which is consistent with either king (Neh 2:1; 5:14; 13:6). The alignment of the decree with the thirty-second year of Artaxerxes II is therefore meaningful. It is significant circumstantial evidence against the consensus in its own right.

The first milestone is even less straightforward. It is the second year of Darius II, and it marks an unrecorded decree that Darius II issued to refortify Jerusalem. The “historical” date of the second Hebrew vision establishes its timed prediction for the fall of Jerusalem, but this fact alone does not explain why its authors chose it. A parallel human decree in the second year of Darius II is a fair answer to this question, and it may be a necessary one. The very coherency of the seventy sabbatical cycles requires the refortification of Jerusalem to begin no later than AM 3340 = 422/1 BCE, the second year of Darius II. If not, the promised reprieve from destruction is meaningless. Moreover, the earliest possible date for its refortification is AM 3340 = 422/1 BCE, the first year of Darius II. Though Darius I decreed the restoration of the Jerusalem Temple in his second year (Haggai 1:1-2:23), he left the city unfortified, and it remained in this condition throughout the reign of Artaxerxes I (Ezra 4:6-24). The divine decree in the vision, however, dates to this year, and it implies that the city remains unrestored at the time. These bounds therefore leave AM 3340 = 422/1 BCE as the only possible date for the human decree.

Though this decree is unrecorded, it is not a remote possibility. Various anomalies in the biblical book of Ezra-Nehemiah point to its existence. This book documents the postexilic history of Jerusalem, but its narrative presents several notable problems. Among them is its succession of Achaemenid kings, which is Cyrus, Xerxes, Artaxerxes, Darius, and a second Artaxerxes (Ezra 1:1-4:5; 4:6; 4:7-23; 4:24-6:22; Ezra 7:1-Neh 13:31).[45] This list notably has only a single Darius, a Darius who restores the temple after the reigns of Xerxes and Artaxerxes I (Ezra 5:1-6:18). The book therefore conflates Darius I with Darius II, and sets an act of Darius I during the reign of Darius II (Haggai 1:1-2:23). The book also conflates the work on the Jerusalem temple with the refortification of the city itself, and this anomaly may explain the evident error (Ezra 4:7-24; 5:1-6:18). If Darius II ordered the refortification of the city in his second year, the editors of Ezra-Nehemiah may have conflated this act with the decree of Darius I in his own second year, given the identical regnal names and identical regnal years.

The reader should not dismiss the points above without careful consideration. The fact that the seventy sabbatical cycles challenge a consensus on the mission of Nehemiah and imply an unrecorded act of Darius II is not evidence against the present thesis. Any such argument has the logic backward: The success of the seventy sabbatical cycles is so remarkable that the present consensus on Nehemiah is almost certainly wrong, and the proposed decree of Darius II almost certainly occurred. Regardless of modern opinion, the relevant biblical dates themselves are ambiguous: The first can refer to either Darius, and the second can refer to either Artaxerxes. The alignment of the decree with the second year of Darius II and the thirty-second year of Artaxerxes II is therefore an alignment with the biblical dates. The view that this match is random is too improbable to accept as a serious hypothesis: Once more, authorial intent is clearly the superior position. The authors of the Hebrew Daniel simply held a different position than many modern scholars, and this position is probably right. These points, then, do not expose any weakness in the present thesis. They instead show its evident power to clarify troubling problems in biblical chronology and the text of Ezra-Nehemiah. For other theses, similar power to clarify unrelated problems is widely accepted as an indication of truth.

Another unrelated problem that this thesis may clarify is the cycle of Jubilee years during the Second Temple period (Lev 25:8-55). Both the Jubilee and the sabbatical year draw upon antecedents in Ancient Near Eastern culture that identify them as periodic rededications of the land of Israel as the sacred precinct of the temple, and the Israelites as the citizens of that precinct.[46] This hypothesis ties the current cycle of sabbatical years to the foundation of the Second Temple, and the date of that foundation does align with the current cycle. The reconstruction of the Second Temple began in the “sixth month” of the second year of Darius I, which in the Babylonian calendar was the year AM 3242/3 = 520/19 BCE (Hag 1:1,15; 2:10).[47] The Behistun Inscription implies that Darius became king on September 29, 522 BCE, which in the Hebrew calendar falls in the year AM 3240.[48] In either calendar, then, the foundation of the Second Temple occurred in the year AM 3242, which in the current cycle of sabbatical years was the first year of a count. The second year of Darius II, AM 3340 = 422/1 BCE, is the ninety-eighth year after this foundation. Since there is no historical evidence that the Jubilee ever interrupted the cycle of sabbatical years, this figure implies that the second year of Darius II was a Jubilee, and that the seventy sabbatical cycles constitute ten perfect Jubilee cycles. The first seven sabbatical cycles also mark the first of those Jubilee cycles. Given the significance of the Jubilee to the holiness of the temple and its precinct, the refortification of Jerusalem in a Jubilee and its ultimate destruction in a Jubilee hardly seems accidental. This alignment also affirms the continuity of the current cycle since the foundation of the Second Temple, against which there is no compelling evidence.[49]

A final, critical point is how this analysis rests on errors in Ezra-Nehemiah. Given this fact, few people committed to the inerrancy of the biblical text would adopt it, even if they recognized its remarkable alignments. The entity behind the Hebrew visions also permitted the errors in Ezra-Nehemiah, despite its evident power to ensure the inerrancy of the book. From these implications we may draw two important conclusions. First, the entity behind the Hebrew visions did not intend any true believers in biblical scripture to decipher their meaning. Second, this entity not only does not care about the accuracy of the Hebrew Bible, but it actually created the Hebrew visions to emphasize some of its inaccuracies. Whatever this entity is, it is not the common conception of the biblical God.

Table 5. Milestones in the Seventy Sabbatical Cycles | ||||

Cycle | Year | AM | BCE/CE | Significance |

0 | 7 | 3339 | 423/2 BCE | “First year of Darius ben Xerxes” The first year of Darius II (Dan 9:1). |

1 | 1 | 3340 | 422/1 | Second year of Darius II Darius II refortifies Jerusalem (Dan 9:25). |

3 | 7 | 3360 | 402/1 | “Third year of Cyrus, king of Persia” Cyrus the Younger invades Mesopotamia (Dan 10:1-3,20). |

6 | 3 | 3377 | 385/4 | Twentieth year of Artaxerxes II Egyptian or allied forces attack Jerusalem. Nehemiah is sent to refortify the city (Neh 1:1-2:8). |

7 | 7 | 3388 | 374/3 | End of first seven cycles |

8 | 1 | 3389 | 373/2 | Thirty-second year of Artaxerxes II Nehemiah returns to the court of Artaxerxes II (Neh 5:14; 13:6). The High Priest achieves great prominence (Dan 9:25). |

69 | 7 | 3822 | 61/2 CE | End of the sixty-two cycles |

70 | 1 | 3823 | 62/3 CE | Start of the sixty-two cycles Lucceius Albinus and Herod Agrippa II depose Ananus ben Ananus from the high priesthood, after Ananus executes James, brother of Jesus. (Dan 9:26; Josephus, Ant. 20.197-203). |

70 | 4 | 3826 | 65/6 | Middle of the final cycle Sacrifices for the Roman emperor end at the Jerusalem temple, starting the First-Jewish Roman War (Dan 9:27; Josephus, J.W. 2.409). |

70 | 7 | 3829 | 68/9 | End of the seventy sabbatical cycles |

71 | 1 | 3830 | 69/70 | |

Large Numbers and Aramaic Prophecies

The original, Aramaic core to the Book of Daniel has two prophecies notable for their eschatological purpose. The first opens the Aramaic core, and the second closes it. The first prophecy is the dream interpretation in the first court tale, which concerns the vision of the multimetallic idol and the stone that destroys it (Dan 2:31-45). The second is the vision of the four beasts from the sea and the little horn (Dan 7:1-28). These two prophecies are parallel narratives with parallel elements: Both predict the emergence of a final, eternal, and divine empire following the rise and fall of four successive human empires (Dan 2:44-45; 7:11-14, 27). In the first prophecy, the four metals of the idol symbolize the four human kingdoms, and in the second, it is the four beasts.

In their isolated form, these prophecies depict the fictional history of the court tales, augmented with an unseen, fourth kingdom. They do not depict actual events. Daniel explicitly identifies the golden head of the idol with the fictionalized Nebuchadnezzar, setting the first kingdom firmly within the fictional narrative (Dan 2:37-38). This identification implies that the second kingdom of silver is the kingdom of Darius the Mede, and the third kingdom of bronze is the kingdom of Cyrus (Dan 5:31-6:28).[50] As for the fourth kingdom of iron, it is a complete fiction. It only serves the evident eschatological scheme of a post-present tribulation before the apocalyptic revelation of an age to come.

Apart from the Hebrew Daniel, this fourth kingdom does not signify the Classical West, or any part of it. Aside from its placement after the kingdom of Cyrus, nothing in the Aramaic Daniel clearly ties this kingdom to Alexander, his successors, or Rome. Nowhere does either prophecy mention “Ionia” or “Kittim,” both references to the ancient West used in the Hebrew Daniel (Dan 8:21; 10:20; 11:2,30). The fourth kingdom does break apart like the empire of Alexander, but it is divided among ten kings, three of whom fall to an eleventh, the little horn (Dan 2:41; 7:7-8,24-25). Nothing in this drama clearly matches (without serious strain) the successors to Alexander or Rome.

Given its persecution of the Jewish people, many commentators wrongly identify the little horn as the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (Dan 7:25). Though this inference is not unreasonable, Antiochus simply does not fit the details of the little horn. He was never a “little” person, he was not the eleventh Seleucid by any reasonable count, and he did not unseat three kings to seize his throne.[51] A persecution of the Jewish people is also not unique to Antiochus. The theme of persecution is common in both Jewish history and literature, most notably in the Exodus account itself. The mere mention of persecution, then, does not imply a historical parallel. Moreover, the persecution under Antiochus does not match the vision. In the vision the little horn persecutes the Jewish people for a “time, two times, and half a time,” or three and a half years (Dan 7:25). The war Antiochus started against Judea lasted five years, with Antiochus himself dying four years after it began (1 Macc 1:54; 4:52; 6:16,20; BM 35603).[52] Hasmonean forces also rededicated the temple exactly three years after its desecration (1 Macc 1:54-61; 4:52).[53] To be sure, both the prophecy and the ancient sources on Antiochus may suffer from historical errors, so a perfect match with the little horn is hardly needed to confirm this hypothesis. These discrepancies are nevertheless too many to accept this reading of the vision without a reasonably precise time for its accomplishment, and even then, the reading would remain doubtful.

The fourth kingdom in both prophecies, then, is best understood as an imaginary final empire, the creation of which predates the rise of Alexander. Literary motifs and numerical symbolism are better explanations for its details than actual events. Apart from the succession of four kingdoms, nothing in either prophecy times its emergence, yet this succession is a known, pre-Hellenistic literary motif. As others have noted, Hesiod, in Works and Days, employed nearly the same scheme as the first prophecy, including the same four metals (Hesiod, WD 109-176). This poem dates to the seventh-century BCE, and Hesiod may have even drawn on an earlier Persian source, dating this scheme to well before Alexander and the Aramaic Daniel. Many details and numbers in the second prophecy are also round or symbolic. In Aramaic, the lion (אריה), bear (דב), and leopard (נמר) stand in their alphabetical order. The numbers tied to them also emphasize this order: The lion has two wings, the bear is grinding three ribs, and the leopard has four heads and four wings. The ten horns have a round number, and the displacement of three kings by the little horn produces the symbolic combination of the numbers seven and eight (cf. Mic 5:5). As for the “time, two times, and half a time,” the period of three and a half years is exactly half of seven.

The addition of the Hebrew Daniel changes this exegesis of the fourth kingdom, grounding its identity in actual history. With the Hebrew Daniel, the idol in the first prophecy becomes an outline of the entire book, and its fourth kingdom positively becomes the Classical West from Alexander through Rome. Its iron legs and feet gain an actual, historical meaning that they lack in the isolated Aramaic Daniel. Given this change, the rock that strikes these legs and feet also assumes a historical meaning: It signifies the rise of Islam. In this interpretation the iron specifically corresponds to the Byzantine Empire, the final phase of the classical West, and the clay specifically corresponds to the Sasanian Empire, the final phase of ancient Persia. The strike of the stone signifies the Arab conquests, the end of ancient Persia, and the reduction of the Roman Empire to a medieval Greek kingdom. The destruction of the idol also signifies the strict Islamic opposition to idolatry, and the key role that the Arab conquests play in the decipherment of the book. The idol represents the book, and its destruction signifies its decipherment. The growth of the rock into a great mountain signifies the foundation of the Caliphate as an eternal kingdom of God.

A key element of the Hebrew Daniel reinforces this interpretation. That element is the prominence of the millennium-long conflict between the classical West and ancient Persia. This prominence is obvious in the symbolic and overt references to the conquests of Alexander (Dan 8:2-7; 11:2-4), but it is also evident in the name “Darius ben Xerxes,” which only makes sense in the context of this conflict (Dan 9:1). The very purpose of this name is to distinguish Darius II from Darius I, the first Persian king to attack Greece, and the notability of Xerxes as the second Persian to do so justifies the atypical avonymic. Darius II is the grandson of the well-known Xerxes, not his better-known father, Darius I. Introducing the Arab Conquests completes this theme: The rise of Islam brought this interminable ancient conflict between the ancient West and ancient Persia to an end. The final war between them was the Byzantine-Sasanian War of 602-628, which preceded the rise of Islam and contributed to its success.

The effect of the Hebrew Daniel on the second Aramaic prophecy is remarkably different. Despite the common meaning of the first and second prophecies apart from the Hebrew Daniel, the second Aramaic prophecy identifies modern Israel, not the Caliphate, as the eternal kingdom of God. The interpretation of the rock in the first prophecy as Islam is only possible because the first prophecy makes no direct mention of the Jewish people. The second prophecy, on the other hand, does reference them and attributes the eternal kingdom to them, not to Muslims (Dan 7:7,22,27). The third Hebrew vision also incorporates the “time, two times, and half a time” of the second prophecy into actual history. According to the final scene of the book, a great tribulation for the Jewish people follows the destruction of Jerusalem, and the “time, two times, and half a time” is the culmination of this era (Dan 12:1-7). Given the success of the seventy sabbatical cycles, it is reasonable to assume, for the sake of argument, that history actually accomplished this prediction. If so, the event that accomplished it should reverse at least some of the consequences of the First Jewish-Roman War, among which were the loss of Jewish political authority in the land of Israel, and the exile of the diaspora. The only historical event that largely fits these criteria is the creation of modern Israel. Moreover, if modern Israel does mark the end of the great tribulation, then the “time, two times, and half a time” is some persecution associated with its emergence, and that persecution would be the Holocaust. The third Hebrew vision, then, implies that Israel, not the Caliphate, is the eternal kingdom of God.

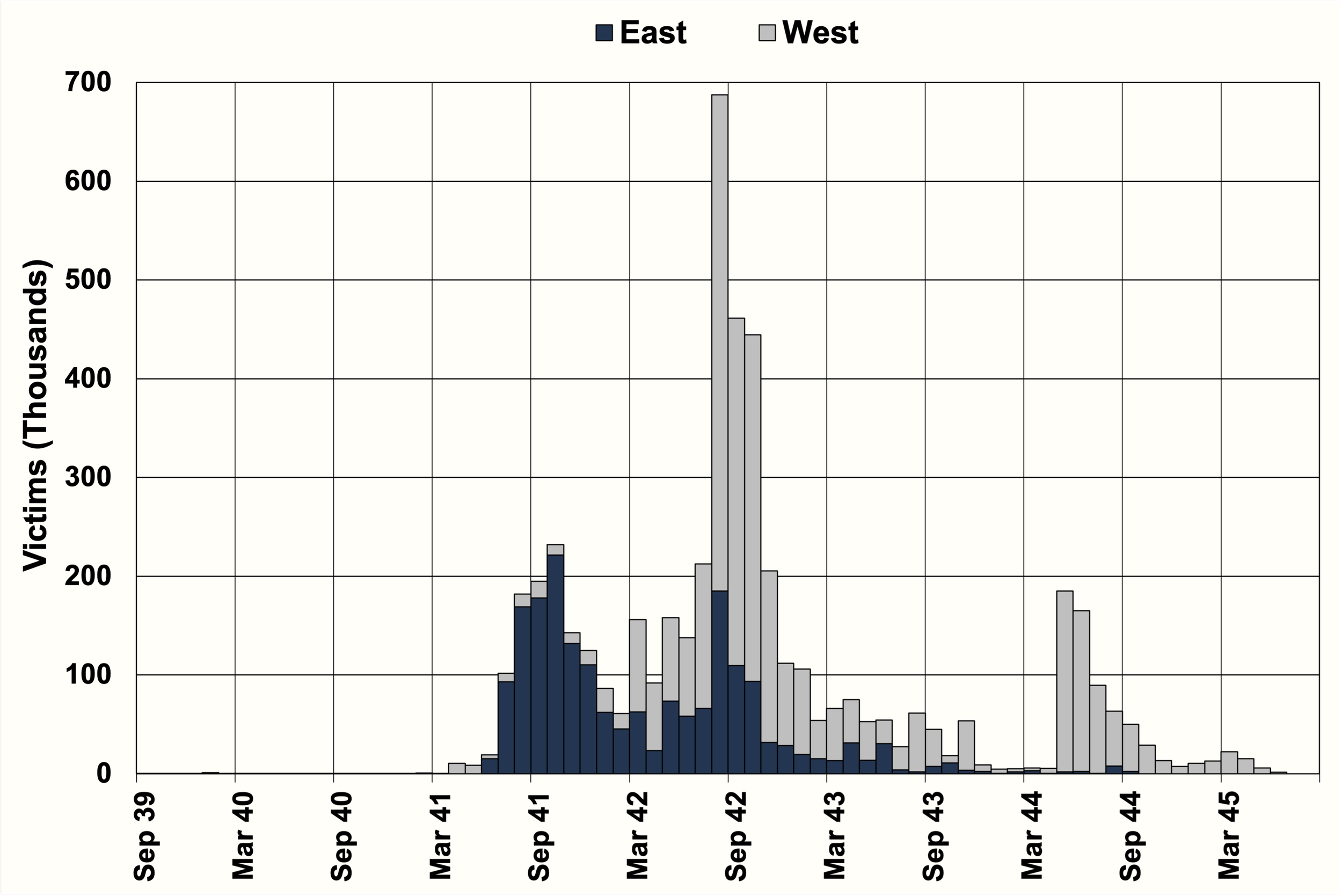

Figure 1. Time profile of Holocaust murders during World War II (East and west of the June 1941 Soviet frontier)[54] |

The alignment between this hypothesis and the text of the second prophecy is remarkable, even if this alignment alone is insufficient to confirm it. This prophecy has a plausible interpretation that ties it to World War II, the rise of Adolf Hitler, the Holocaust, and the establishment of Israel. Though the “great sea” in the vision is a clear reference to the Mediterranean, we may also read it as “the greater West,” since “sea” also means “west” in biblical Hebrew (a sense we may extend to Jewish Aramaic). The four beasts therefore signify Western “kingdoms” that emerge from some great turbulence, which we may read as World War I. The first three beasts are the principal allies in World War II. The lion is a national symbol of England (and by association the United Kingdom), and the bear a symbol of the Soviet Union. The leopard is not a symbol of the United States, but it is a phonetic pun on one: “eagle” (נשר, něšar) and “leopard” (נמר, němar) differ by a single, medial consonant in Aramaic.[55] The fourth beast represents post-imperial Germany, the little horn signifies Adolf Hitler, and the ten horns signify the ten chancellors that ruled during his political rise, beginning with his discharge from the German army on March 31, 1920.[56] The three horns the little horn displaces signify the three chancellors whose governments Hitler undermined to achieve total power: Heinrich Brüning, Franz von Papen, and Kurt von Schleicher.[57] The many words of the little horn signify Hitler’s well-known oratory, and its eyes signify his documented use of a dramatic stare to project an overwhelming presence. In the words of William L. Shirer:

It was the eyes that dominated the otherwise common face [of Hitler]. They were hypnotic. Piercing. Penetrating. As far as I could tell, they were light blue, but the color was not the thing you noticed. What hit you at once was their power. They stared at you. They stared through you. They seemed to immobilize the person on whom they were directed, frightening some and fascinating others, especially women, but dominating them in any case. They reminded me of paintings I had seen of the Medusa, whose stare was said to turn men into stone or reduce them to impotence. All through the days at Nuremberg I would observe hardened old party leaders, who had spent years in the company of Hitler, freeze as he paused to talk to one or the other of them, hypnotized by his penetrating glare. I thought at first that only Germans reacted in this manner. But one day at a reception for foreign diplomats I noticed one envoy after another apparently succumbing to the famous eyes. Martha Dodd, the vivacious young daughter of the American ambassador, had told me a day or two before I left for Nuremberg, to watch out for Hitler’s eyes. “They are unforgettable,” she said. “They overwhelm you.”[58]

The “time, two times, and half a time” signify the Holocaust, and the relative timing of its three pulses of murder, shown in Figure 1. These three pulses more or less divide the three and a half year period from the commencement of Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941 to the liberation of Auschwitz on January 27, 1945 into subperiods of a year, two years, and half a year. Given this basic structure of the Holocaust, it permits several plausible alignments with a “time, two times, and half a time.”[59]

The most logical alignment identifies it as the period from 1 Tishri 5702 = September 22, 1941 to 1 Nisan 5705 = March 15, 1945. A divine court is a prominent feature of the Aramaic prophecy, and Rosh Hashanah (1 Tishri) is the first day of the Days of Awe, when the Jewish people traditionally stand before God in judgment (Dan 7:9-10). This reading also aligns each time segment with a pulse of murder, which matches the description of this period in the Hebrew Daniel as “a festival, two festivals, and half [a year]” (Heb.: מועד מועדים וחצי) (Dan 12:7). This reading also aligns the fall of Nazi Germany with Passover, the traditional Jewish celebration of liberation. As for the kingdom that the Jewish people receive after these events, logic suggests a reference to modern Israel. (This reference neither legitimizes nor delegitimizes the state).

Despite the incoherence of these two interpretations of the kingdom of God (and their evident incorrectness), the prophecies of the large cryptic numbers show that both interpretations are intentional. The motivation for these numbers lies in the first Aramaic prophecy. In the interpretation of that dream, Daniel states that “in the days of those kings,” that is, the kings of the iron legs and feet, “the God of heaven will set up a kingdom that shall never be destroyed” (Dan 2:44). The prophecies of the cryptic numbers are a play on this verse: Each number counts a period of “days,” and these “days” bound the commentary that addresses these kings of the iron legs and feet. The prophecies of the cryptic numbers are “the days of these kings” that time when God establishes an eternal kingdom, and these numbers direct us to both the Caliphate and Israel.

The three cryptic numbers in the Hebrew Daniel are remarkable for their size, their precision, and their lack of any evident symbolism. The three numbers are two thousand three hundred, one thousand two hundred and ninety, and one thousand three hundred and thirty-five (Dan 8:14; 12:11-12). All three number a period of “days,” though the unit of the first number has been lost in the Hebrew text. Both the Old Greek (Septuagint) and Theodotion, ancient Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible, preserve the unit “days” (Dan 8:14, NETS).[60] While these three numbers are not the largest or the most precise in the Hebrew Bible, their size and precision are nonetheless odd for a time expression. Time expressions are often round, and they typically have units that minimize the numbers in the expressed duration. To be sure, long periods of days are not unknown in the Hebrew Bible. The feast of Ahasuerus lasted one hundred and eighty days, and Ezekiel prophesied a siege against Jerusalem for three hundred and ninety (Esth 1:4; Ezek 4:5,9). Both of these figures, however, are less than a thousand, and both are round: They are both multiples of thirty, the ideal length of a month. Of the three numbers in Daniel, all are greater than a thousand, and only one thousand two hundred and ninety is a multiple of thirty. Any traditional symbolism is also absent from these three numbers. None of them are multiples of seven, twelve, or forty. Instead, they have unusual factors like twenty-three, forty-three, and eighty-nine. For contrast, the Revelation represents the “time, two times, and half a time” as one thousand two hundred and sixty days, which is a multiple of seven, twelve, and thirty (Rev 11:3; 12:6). The Codex Alexandrinus, a fifth-century copy of the Septuagint, likewise emended the number two thousand three hundred to two thousand four hundred, which is divisible by twelve, thirty, and forty (Dan 8:14, Brenton LXX). This figure is both round and symbolic. Given these facts, the three large numbers in Daniel seem to express actual, precise periods. Their very natures exclude simpler, literary hypotheses.

The first of the three numbers aligns with the Six-Day War. The prophecy of this number in Hebrew and in English translation is:

ואשמעה אחד קדוש מדבר ויאמר אחד קדוש לפלמוני המדבר עד מתי החזון התמיד והפשע שמם תת וקדש וצבא מרמס ויאמר אלי עד ערב בקר אלפים ושלש מאות ונצדק קדש

Then I heard a holy one speaking, and another holy one said to whoever was speaking, “How long is the unceasing vision and the transgression, its desolation of a holy place and trampled ministrants?” Then he said to him, “Until an evening is a morning, there will be two thousand three hundred days. Then a holy place will be put right.” (Dan 8:13-14)